Background

TA Towers ApS (“TA Towers”), a company based in Denmark, is the holder of the below registered Community design relating to goods for building materials, specifically, ‘building materials for a windmill tower’ (the “RCD”):

On 3 September 2019, the intervener, Wobben Properties GmbH (Wobben) filed an application for a declaration of invalidity of the RCD. Wobben claimed that:

- the contested design lacked novelty,

- it did not have individual character, and

- the features of its appearance were solely dictated by their technical function.

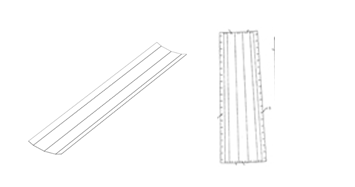

Wobben relied (among others) on drawings from earlier patent applications (as seen below) as relevant prior art.

image 1 – A tubular tower and construction procedure (WO 2010/055535 A1)

On 20 November 2020, the Cancellation Division held the RCD to be invalid on the grounds that it lacked individual character against the design shown in the international patent application (image 1). That decision was upheld on appeal to the EUIPO Board of Appeal (the “Board”).

TA Towers appealed to the General Court (the “GC”), arguing that the Board had erred in its assessment of the individual character of the contested design, in particular:

- the definition of the “sector concerned”,

- the definition of the “informed user”, and

- the finding relating to the “overall impression” produced by the contested design against the prior art.

The GC’s Judgment

(i) The sector concerned

By way of re-cap, the individual character of a registered design is to be judged by reference to the sector of the product in which the contested design is intended to be incorporated or to which it is intended to be applied. The sector of the product is a relevant consideration for determining the informed user and his or her level of attention, and for determining the designer’s degree of freedom in developing the design. When determining the sector concerned, the court will consider two factors: (i) the indication of the products as set out in the application for registration, and (ii) the design itself, in so far as it specifies the nature of the product, its intended purpose or its function which can be gathered from the visual representations and any description accompanying the application for registration.

TA Towers argued that the Board had defined the “sector concerned” with the incorrect assumption that the RCD was meant for assembly with identical elements only, to form a conical cylinder similar to that shown in the prior art. It said the RCD shows one building element which may be linked to elements of other sizes or dimensions that would not necessarily result in forming a conical cylinder. It argued that the Board had failed to take this into account in assessing how an “informed user” would perceive the RCD.

The GC rejected this part of the plea. The “relevant sector” had to be based on the representation and indication of the design as shown on the register, irrespective of the range of products to which it might be possible to apply it. The applicant had described the RCD as showing ‘building materials for a windmill tower’. Although it did not expressly say so, the Board had correctly considered the sector of ‘segments for towers’. The fact that the prior art showed an entire tower consisting of various elements to form a conical tower, whereas the RCD consisted of only one segment for a tower, had no bearing on the assessment of the sector. Put simply, the fact that other assemblies were possible did not change the fact that regular use (as intended) of the RCD would result in an assembled product in the shape of a conical cylinder.

(ii) The informed user

TA Towers argued that the informed user must display a high level of attention, as the relevant sector was limited and highly specialised.

The GC rejected this part of the plea. The informed user is defined in general terms as lying somewhere between that of the average consumer without any specific knowledge, and the sectoral expert who is an expert with detailed technical expertise. That determination could not be made on a case-by-case basis in relation to a particular design.

The GC found that the Board was entitled to take the view that the informed user was a professional in the construction sector who had some knowledge of the different segments for towers and displayed a relatively high level of attention. However, it could not be held that the informed user was “fully aware” of the details of all the designs available on the market in those segments.

(iii) The comparison of overall impression

The applicant had more success in contesting the Board’s findings on “overall impression” between the RCD and the prior art.

The GC upheld the appeal on the basis of this plea. It held that the Board had erred in its finding that the RCD and the prior art shared the features of a sheet of a rectangular elongated shape comprised of a number of bends extending in a longitudinal parallel direction, differing only in the number of bends (the RCD contained only three bends, whereas the prior design contained four.)

The GC held that:

- The Board had erred in finding that the sheet of the prior art was “rectangular”, because the bends at the end of the sheet of the prior design were of different lengths. Although the difference was not large, from the illustration of the prior design it was clearly visible.

- By contrast, the sheet of the RCD is rectangular. Consequently, the shape of the sheet of the prior art differed from that of the RCD. The informed user who is a professional in the construction sector with a relatively high level of attention would perceive that difference, as the shape of the sheet is one of the most visible and important elements which allows the informed user to form an idea of what the final towers will look like once the sheets are assembled. The informed user would be aware that, due to the sheets' differing shape, the RCD would produce a cylinder, whereas the prior design would produce an element corresponding to a truncated cone.

- Even though the difference in the number of bends between the designs was not sufficient, on its own, to produce a different overall impression in the mind of the informed user, that user would take note of that difference and be aware that the final towers would also have slightly different shapes for that reason.

- Since the shape of the sheets and their number of bends had a significant influence on the overall impressions produced by the RCD, the differences perceived in that regard by the informed user were sufficiently marked to avoid any impression of "déjà vu". The informed user would conclude that the RCD creates a different overall impression despite the existence of similarity in respect of other aspects (such as the vertical bends creating parallel panels).

Comment

The key take-away from this decision is that the “overall impression” of a registered community design for a building component can, in some cases, take into account the appearance of the final assembled product (as the informed user would perceive it) even though it does not appear on the register. The court may compare a design for an individual component with prior art showing a partly or fully assembled product, provided the designs belong to the same sector. This is likely to apply only where it is clear that the design is meant to be assembled from identical elements, so that the court can determine the shape of the final product.

It is also prudent for community registered design applicants to accurately state the indication of the product when filing an application for registration. Although the indication of the product will not necessarily dictate the court’s assessment, it can help minimise uncertainty about the nature of the product and the “sector concerned”, particularly where the design relates to a building component.

It is also notable that the GC took into account the product description provided by TA Towers for its RCD, being “building materials in the form of a segment for wind turbine towers”. EUIPO guidelines state that an RCD application “may” include a description explaining the representation of the design, but that the description will be irrelevant to the scope of protection. (This is to be distinguished from the ‘indication of the product’, which is mandatory). Nevertheless, in this case, that description appears to have been taken into account by the GC in assessing the “individual character” of the RCD against the prior art. Therefore, whilst descriptions are not mandatory and may well be disregarded, design applicants should still consider including suitable descriptions where the nature and purpose of their design may not be immediately apparent from the images and the product indication.

Social Media cookies collect information about you sharing information from our website via social media tools, or analytics to understand your browsing between social media tools or our Social Media campaigns and our own websites. We do this to optimise the mix of channels to provide you with our content. Details concerning the tools in use are in our privacy policy.