The German Act on the Implementation of the EU Mobility Directive (UmRUG) offers new structuring options and introduces changes to cross-border mergers as well.

The entry into force of the German Act on the Implementation of the EU Mobility Directive (UmRUG) on 1 March 2023 was eagerly awaited, as it now regulates cross-border changes of legal form and cross-border splitting/spin-offs for the first time.

However, UmRUG also results in a number of changes for cross-border mergers, for which harmonised provisions within the EU and the EEA have been in place since 2007. It is therefore also worth taking a closer look at these.

Cross-border mergers – good option for many reasons

Cross-border mergers have been used very frequently in practice since they were implemented EU-wide. The first indications since the UmRUG came into force show that this trend is continuing.

There are many reasons for a cross-border merger. Based on experience and our observations, the main drivers are the following:

- streamlining the group structure/consolidating the shareholding structure: such streamlining/integration can be particularly useful after acquisitions,

- reducing administrative expenses in the group: synergies can be utilised and costs can be reduced,

- establishing a European regime for employee participation,

- optimising cash management: in a structure with dependent EU/EEA branches, it may be easier to distribute and manage liquidity than with several independent group companies; this can be an alternative to cash pooling.

In comparison to a transfer of individual assets, a merger also has the advantage of universal succession. All rights and obligations can generally be transferred without requiring the consent of third parties. Unlike a transfer of individual assets, a merger can also be implemented without incurring corporate income taxes.

Cross-border mergers also still possible outside the EU and EEA

The EU Mobility Directive still generally only allows cross-border mergers within the EU and EEA. Cross-border mergers with some other countries are also possible in a few jurisdictions, such as Austria and Luxembourg. From a German perspective therefore, it will continue to be possible to merge with companies from non-EU/EEA countries after the UmRUG comes into force, but only via a merger into one of those EU jurisdictions.

For example: a Swiss company merges with an Austrian company and is then merged with a German company under the EU Mobility Directive.

A very familiar process with interesting new features

Unfortunately, even after the UmRUG came into force, it is still only corporations/limited liability companies that are permitted to participate in cross-border mergers. Partnerships can only act as absorbing legal entities in an inbound merger into Germany, and only if they do not have more than 500 employees on a regular basis.

The basic process is still essentially broken down into the three familiar components:

(1) preparation - (2) resolution - (3) review of legality. However, it is necessary to pay special attention to the following aspects since the UmRUG came into force:

- Protection of minority shareholders

Minority shareholders are entitled to exit the company in return for cash compensation. Shareholders also have the right to comment on the draft terms of the merger up to five working days before the merger resolution.

In addition, minority shareholders from both of the companies involved can now only raise a claim to improve the exchange ratio through a minority shareholder action. For a stock corporation, a European company (SE) or a partnership limited by shares (KGaA), this right can also be fulfilled by granting new shares instead of by making an additional cash payment if this is already provided for in the draft terms of the merger.

- Creditor protection

Under certain conditions the creditors of the entity being acquired can demand security. Now, it is necessary to assert a claim in court within three months of the draft terms of the merger being published in the register. It is no longer sufficient to assert the claim against the company, like in the past. The merger cannot be registered until this creditor protection period expires or until a court dispute in this respect has been resolved.

Creditors also have the right to comment on the draft terms of the merger up to five working days before the merger resolution.

- Strengthening employee rights

In future, the merger report must be made available electronically to the works council or the employees six weeks before the merger resolution is passed (previously four weeks). The works council or the employees also have the right to comment on the draft terms of the merger up to five working days before the resolution is passed.

- Monitoring function of the commercial register

The commercial register now has to check for indications of an abuse of process. The registry court is required to make further enquiries if there are indications of abusive or fraudulent purposes of the cross-border merger. This can significantly delay the process or even prevent registration of a merger altogether. The Act contains examples of such indications, but these are not exhaustive.

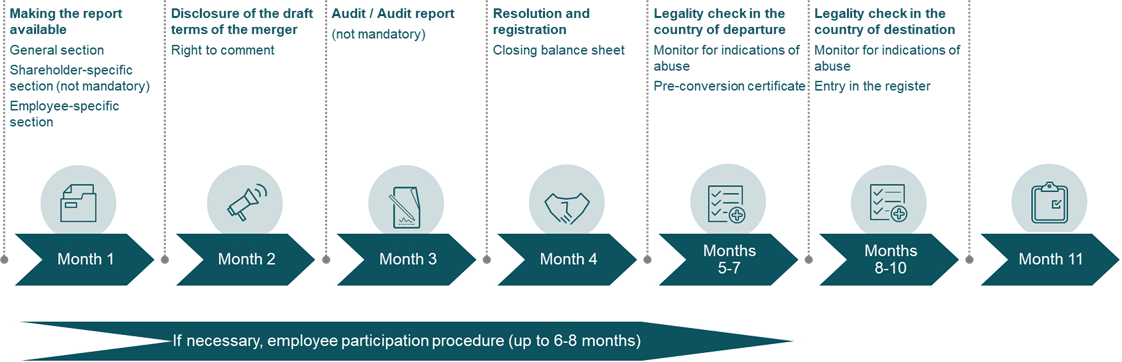

Approx. 8 to 12 months should be planned for a cross-border merger, depending on the circumstances. The basic procedure for a cross-border merger is as follows:

Protecting employee participation rights

Protecting employee participation rights is of particular importance in the context of a cross-border merger. Employee participation in this respect means the rights of employees to appoint some of the members of the supervisory board or administrative board of the company or to recommend or oppose such appointments.

Companies should not be able to prevent this type of employee participation by moving their registered office through a cross-border merger to an EU/EEA country where the national regulations provide for a lower level of employee participation or no employee participation at all. Therefore, an employee participation procedure must be carried out under certain conditions, with the aim of negotiating and reaching an agreement on employee participation between management and the employees (represented by a special negotiating body).

If it is not possible to reach an agreement, a statutory fall-back solution applies which ensures the participation scenario previously applicable will continue ("before and after principle"). Negotiations can last up to six months or even a year if there is a mutual agreement to extend negotiations.

This "negotiated solution" is based on the system under SE law. However, the new EU Mobility Directive provides even greater protection for employee participation rights. The German Act on Employee Participation in Cross-Border Mergers (MgVG) has undergone significant changes to this end.

Requirements for the participation procedure

Now, for cross-border mergers, an employee participation procedure must be carried out if one of the companies involved

- already had employee participation or

- employed at least four-fifths of the employee threshold number for employee participation under the law of the departure state or destination state.

The four-fifths rule is new. Its aim is to prevent companies from implementing a cross-border merger to avoid employee participation just before they reach the relevant threshold. If negotiations fail, the statutory fall-back solution does not generally result in employee participation in this case. The status is then also "frozen" subject to subsequent conversions.

If one of the companies involved already had employee participation before the cross-border merger, the management of the companies involved can still decide to "skip" the employee participation procedure and have the standard statutory rules apply. Employees or employee representatives cannot prevent this decision, as it ultimately does not lead to a reduction of the employee rights. The employee participation status achieved in this manner is also frozen subject to subsequent conversions.

Safeguarding participation rights by monitoring an abuse of process

Companies that reach at least four-fifths of the relevant national threshold for employee participation will therefore find it more difficult to implement cross-border mergers. They have to carry out a procedure to safeguard participation rights, even though such participation rights do not exist (yet).

German lawmakers have created yet another obstacle for such companies: An indication for an abuse of the procedure for cross-border mergers would be

if the number of employees is at least four-fifths of the relevant threshold for employee participation, no value is added in the target country and the head office remains in Germany.

This provision for monitoring an abuse of process is not required under the EU Mobility Directive. It is likely to be contrary to EU law. Nevertheless, it is now necessary to take this into consideration in the relevant scenarios.

Don't forget taxation!

In addition to the requirements under the law on conversions, the tax requirements for the intended tax neutrality of the conversion in both the country of departure and the target country must also be reviewed and any divergent tax provisions must be coordinated accordingly (e.g. on retroactive effect of the merger for tax purposes).

Based on the German rules, cross-border mergers between corporations/limited liability companies can generally be carried out at book values for tax purposes, i.e., tax-neutral for the purposes of corporate income tax and trade tax. However, cross shareholdings or cross claims may lead to unwanted tax effects. In certain cases, there may also be a change in the allocation of individual assets to the foreign parent company of the acquiring company as a direct or indirect consequence of the merger (including subsequent integration measures), with the result that exit tax is triggered in this respect.

Furthermore, unutilised current tax losses or tax losses carried forward of the transferring company on the merger date cannot be taken over by the acquiring company, i.e., this potential to offset tax losses is lost without replacement if and to the extent that such losses cannot be offset against a transfer profit. Unutilised tax losses may also be lost at the level of the acquiring company and at the level of direct or indirect subsidiaries of the transferring or acquiring companies due to a change in the direct or indirect capital relationships (> 50%).

Furthermore, tax neutrality and retroactive taxation for corporate income tax purposes do not automatically apply to other types of tax. This is the case in particular with real estate transfer tax. If the transferring company itself or one of its direct or indirect subsidiaries holds German real estate, this may lead to unwanted tax burdens.

Number of cross-border mergers will continue to increase

Overall, when planning a cross-border merger, it is always advisable to carry out a careful review of the implications under corporate law, employment law and tax law. Despite the complexity, cross-border mergers will continue to increase after the new provisions came into force and will continue to establish themselves as a common reorganisation measure.

Social Media cookies collect information about you sharing information from our website via social media tools, or analytics to understand your browsing between social media tools or our Social Media campaigns and our own websites. We do this to optimise the mix of channels to provide you with our content. Details concerning the tools in use are in our privacy policy.